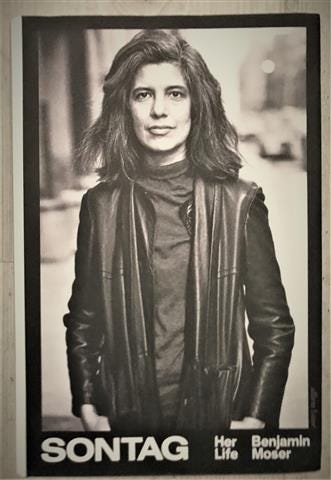

"A Woman Bigger Than Life" - Sontag by Benjamin Moser

Two women taught me to think. Simone de Beauvoir and Susan Sontag. Both women had a great influence on me. I discovered Simone de Beauvoir early in my life. She taught me what it means to exist as a woman in a world dominated by men.

I found Sontag later. The first of her books that I read was the AIDS and its Metaphors. The idea behind this book, and later on her Illness as Metaphor, is that society’s response to diseases that it does not yet understand is to construct fantasies and stigma about them. It was this stigma that literally killed because it discouraged patients from asking the proper questions and seeking the treatment that might save their lives. The only way to change all this, Sontag argued, is to “rectify the conception of the disease, to demythicize it.” Since we are in the midst of an epidemic, it might be worth mentioning that since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in 1981, 75 million people have been infected with the HIV virus and about 32 million people have died (770,000 only in 2018, according to WHO).

Like Susan Sontag, I spent most of my adolescence in a hurry to read all the books I could find. Like Sontag. I am devoted to the idea of transformation. “I‘m only interested in people engaged in a project of transformation,” Sontag wrote in her journal in 1971. “If the desire for transformation can derive from a lack of positive self-satisfaction, it is also the enemy of self-satisfaction in the negative sense, of smugness and complacency,” argues Benjamin Moser, the author of the Sontag’s biography.

In the 1990s, I found in a second-hand bookstore a small Dell paperback with a front-cover photograph of a young Susan Sontag. It was titled Against Interpretation and it was a series of articles and essays where Sontag analyses popular culture as well as high culture and discusses artists and intellectuals. Sontag had seemingly read everything - from Sophocles to Nietzsche and Camus, Godard, Sartre, Barthes, etc. “Interpretation,” she wrote “is the revenge of the intellect upon art.”

“In most modern instances, interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By refusing the work of art to its content and interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, comfortable.

The philistinism of interpretation is more rife in literature than in any other art. For decades now, literary critics have understood it to be their task to translate the elements of the poem or play or novel or story into something else. Something a writer will be so uneasy before the naked power of his art that he will install within the work itself – albeit with a little shyness, a touch of the good taste of irony – the clear and explicit interpretation of it.” __ Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation.

Susan Sontag taught me not to trust the critics – an irony, as she was herself a critic. She has also change the way I see art, the way I read books and the way I write about books.

After Sontag died in 2004, the focus of attention began to drift away from her work and toward her person. She was a complex person, brave, serious, insecure and unpredictable but she offered us a great gift, “she made thinking exciting.” She had endless admiration for art and beauty – and endless contempt for intellectual vulgarity.

“She impressed generations of women as a thinker unafraid of men, and unaware she ought to be. She stood for self-improvement – for making oneself onto something greater that what one was expected to be. ….. She represented the hope for a tolerant and diverse America that would engage with other nations without chauvinism. She stood for the social role of the artist and showed how the artist might resist political tyranny. And she held out hope for the permanence of culture in a world besieged by the indifferent and the cruel.” __Benjamin Moses, Sontag

Benjamin Moser’s biography of Susan Sontag relies heavily on her diaries and more often than not reveals a person insecure as a woman that deservers our pity rather our envy. But Susan Sontag was a woman that did more things, read more than most of the rest of us do. She was a woman bigger than life.

As the, also brilliant, Janet Malcolm wrote on New Yorker on September 2019, . "the dauntingly erudite, strikingly handsome woman who became a star of the New York intelligentsia when barely thirty, after publishing the essay “Notes on Camp,” and who went on to produce book after book of advanced criticism and fiction, is brought low in this biography."